| In

Spanish America, works of visual culture, be they

churches or chasubles, paintings or parades, came

into being through a complex interplay among people,

materials, and technologies. While patrons defined

the need for works, they depended upon architects,

artists, and craftsmen—a cadre of workers with

specialized knowledge of materials and techniques—to

give their desires form. With the interchange of both

parties, extraordinary and unique, as well as simple

and conventional works of visual culture came into

being.

In

some respects, this “artworld,” this system

of social and economic relationships that underlay

artistic creation, was hardly different than ones

that exist today. In other crucial ways, its practices

were quite distinct. For instance, modern notions

of artistic independence and inspired creation would

have seemed odd to most residents of Spanish America.

Throughout much of the colonial period, patrons played

a key role in the creative process. Their taste was

a decisive force in the final shape of the work. And

without the assurance of paying customers, artists

and craftsmen had little reason to paint a portrait

or cast a coffee pot. Time-consuming and costly works

were almost always commissioned, and wealthy patrons

often preferred works that echoed European styles

and tastes. Ironically, the most celebrated artists

may have been among those most constrained by their

patrons’ demands. In

some respects, this “artworld,” this system

of social and economic relationships that underlay

artistic creation, was hardly different than ones

that exist today. In other crucial ways, its practices

were quite distinct. For instance, modern notions

of artistic independence and inspired creation would

have seemed odd to most residents of Spanish America.

Throughout much of the colonial period, patrons played

a key role in the creative process. Their taste was

a decisive force in the final shape of the work. And

without the assurance of paying customers, artists

and craftsmen had little reason to paint a portrait

or cast a coffee pot. Time-consuming and costly works

were almost always commissioned, and wealthy patrons

often preferred works that echoed European styles

and tastes. Ironically, the most celebrated artists

may have been among those most constrained by their

patrons’ demands.

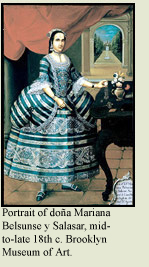

Before

viceregal rule, pre-Columbian societies fostered highly

skilled artisans, among them masons, weavers, painters,

and feather-workers. After the Spanish conquest, however,

the Catholic Church stepped in as an important new

patron. For instance, Europeans regarded with awe

the delicate “painted” images of feathers

that pre-Hispanic craftsmen had created. And soon

after the conquest, Catholic friars set trained specialists

to work, making new kinds of religious vestments and

wall coverings. Their delicate feather mosaics were

works of indescribable skill and beauty, as is this

banner of Christ Pantocrator, “painted”

in central Mexico out of the feathers of tropical

birds. Before

viceregal rule, pre-Columbian societies fostered highly

skilled artisans, among them masons, weavers, painters,

and feather-workers. After the Spanish conquest, however,

the Catholic Church stepped in as an important new

patron. For instance, Europeans regarded with awe

the delicate “painted” images of feathers

that pre-Hispanic craftsmen had created. And soon

after the conquest, Catholic friars set trained specialists

to work, making new kinds of religious vestments and

wall coverings. Their delicate feather mosaics were

works of indescribable skill and beauty, as is this

banner of Christ Pantocrator, “painted”

in central Mexico out of the feathers of tropical

birds.

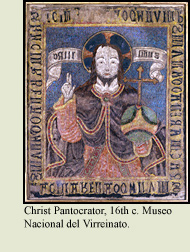

In

other cases indigenous artistry was essential In

other cases indigenous artistry was essential

but less clearly visible as such. The most elaborate

buildings of Spanish America owed their basic designs

to European models and traditions. From Santo Domingo

to Santiago de Chile, cathedrals and the houses of

wealthy Spanish and Creole families as well as some

hospitals and schools depended upon architects well

versed in European styles and techniques. The laborers

who raised these structures, however, were often indigenous.

Sometimes their labor was voluntary, sometimes obligatory.

To create this residence for Francisco de Montejo

on the main plaza in Merida, Maya craftsmen learned

new techniques—in particular for carving stone—to

make the fluted columns, sculpted figures, and broken

pediments.

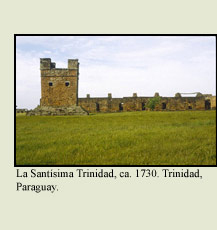

Similar

patterns, in which native craftsmen learned new techniques

to serve colonial needs, were repeated in Mexico,

Peru, Paraguay and elsewhere. The organization and

training of these craftsmen required that knowledge

be passed, largely orally, from generation to generation.

And men rarely worked alone. Women cooked food, provided

clothing and tended fields while men were building.

Native people, sometimes along with African slaves,

were thus responsible—although largely uncredited—for

actually building the vast majority of architectural

projects in Spanish America, be they secular or religious.

Indigenous people, particularly elites and local leaders,

also were important patrons during the colonial period,

commissioning manuscripts, portraits and retablos,

keros, and parish churches. In cities and towns across

Spanish America many of their commissions can still

be seen. Similar

patterns, in which native craftsmen learned new techniques

to serve colonial needs, were repeated in Mexico,

Peru, Paraguay and elsewhere. The organization and

training of these craftsmen required that knowledge

be passed, largely orally, from generation to generation.

And men rarely worked alone. Women cooked food, provided

clothing and tended fields while men were building.

Native people, sometimes along with African slaves,

were thus responsible—although largely uncredited—for

actually building the vast majority of architectural

projects in Spanish America, be they secular or religious.

Indigenous people, particularly elites and local leaders,

also were important patrons during the colonial period,

commissioning manuscripts, portraits and retablos,

keros, and parish churches. In cities and towns across

Spanish America many of their commissions can still

be seen.

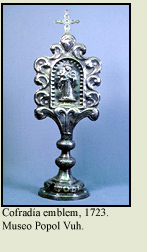

Guilds,

professional associations of skilled craftsmen modeled

on European practices, dominated official artistic

production in Spanish America from the late 16th into

the 18th century. Craftsmanship was the backbone of

the guild system. From Lima to La Paz, from Puebla

to Havana, guilds maintained exacting standards for

quality workmanship. Each guild, among them silversmiths,

painters, and sculptors, had its own cofradía,

or religious society, that often served as a kind

of mutual aid society. And cofradías were a

visible presence in the numerous religious processions

and celebrations that marked the liturgical year,

as members marched together in a show of collective

piety. While many of the works they made or commissioned

for these public displays—like banners, arches,

and floats—no longer survive, other more permanent

ones, like processional crosses and this silver emblem,

hint at the splendid displays city dwellers must have

once seen. Guilds,

professional associations of skilled craftsmen modeled

on European practices, dominated official artistic

production in Spanish America from the late 16th into

the 18th century. Craftsmanship was the backbone of

the guild system. From Lima to La Paz, from Puebla

to Havana, guilds maintained exacting standards for

quality workmanship. Each guild, among them silversmiths,

painters, and sculptors, had its own cofradía,

or religious society, that often served as a kind

of mutual aid society. And cofradías were a

visible presence in the numerous religious processions

and celebrations that marked the liturgical year,

as members marched together in a show of collective

piety. While many of the works they made or commissioned

for these public displays—like banners, arches,

and floats—no longer survive, other more permanent

ones, like processional crosses and this silver emblem,

hint at the splendid displays city dwellers must have

once seen.

Artistic

ideas, models, and styles traveled along many different

paths. Some developed in the colonies, others crossed

from Asia into the Americas. And a great number of

patterns and tastes came from Europe. Books with printed

images and individual prints were copied in church

schools, sold in city markets, and studied in guild

workshops. In 16th-century New Spain, for example,

indigenous painters learned to create European-style

scenes from prints and engravings. And in the 17th

century, architects like Diego de la Sierra (who made

these drawings) sketched Doric and Corinthian columns

as they trained for their guild exams. By 1785, the

royal government founded the Academy of San Carlos

in Mexico City, and dispatched Spanish artists to

teach students, both indigenous and Creole, to draw,

paint, and sculpt following European academic practice. Artistic

ideas, models, and styles traveled along many different

paths. Some developed in the colonies, others crossed

from Asia into the Americas. And a great number of

patterns and tastes came from Europe. Books with printed

images and individual prints were copied in church

schools, sold in city markets, and studied in guild

workshops. In 16th-century New Spain, for example,

indigenous painters learned to create European-style

scenes from prints and engravings. And in the 17th

century, architects like Diego de la Sierra (who made

these drawings) sketched Doric and Corinthian columns

as they trained for their guild exams. By 1785, the

royal government founded the Academy of San Carlos

in Mexico City, and dispatched Spanish artists to

teach students, both indigenous and Creole, to draw,

paint, and sculpt following European academic practice.

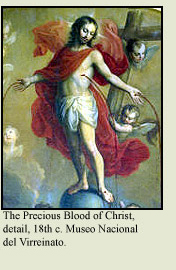

In

cities across Spanish America, the manufacture of

visual culture, like that of the economy at large,

was dependent upon legally sanctioned racial hierarchies

and artificially cheap labor. Guilds had restrictive

laws on the books—they often excluded all but

Creoles and Spaniards from attaining the highest rank

of master artisan—relegating blacks, mulattos

and native peoples to being permanent assistants.

In spite of these rules, some mestizos, such as the

painter, sculptor and architect Bernardo Legarda and

the painter Miguel Cabrera, who painted this mural

for Jesuit patrons, became influential. In Quito,

a Dominican friar established the Confraternity of

the Rosary for indigenous, African, and Spanish artists.

And in Cuzco, native painters formed their own guild.

Thus guilds may have set the tone and guidelines for

artistic production, but they did not circumscribe

all that was created. In

cities across Spanish America, the manufacture of

visual culture, like that of the economy at large,

was dependent upon legally sanctioned racial hierarchies

and artificially cheap labor. Guilds had restrictive

laws on the books—they often excluded all but

Creoles and Spaniards from attaining the highest rank

of master artisan—relegating blacks, mulattos

and native peoples to being permanent assistants.

In spite of these rules, some mestizos, such as the

painter, sculptor and architect Bernardo Legarda and

the painter Miguel Cabrera, who painted this mural

for Jesuit patrons, became influential. In Quito,

a Dominican friar established the Confraternity of

the Rosary for indigenous, African, and Spanish artists.

And in Cuzco, native painters formed their own guild.

Thus guilds may have set the tone and guidelines for

artistic production, but they did not circumscribe

all that was created.

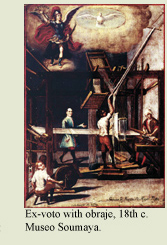

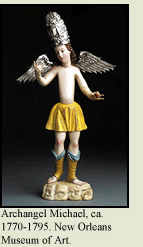

Obrajes—or

factories, largely for the production of textiles—also

benefited from social segregation and debt peonage.

They were staffed with hundreds of indigenous, mestizo,

and mulatto workers. Women, who were usually banned

from guild workshops except as family members, could

also find work in obrajes. While laws required that

they be paid for their work, many obraje workers found

themselves weaving and spinning in servitude, using

their labor to pay off debts that could take years

to erase. Even in this painting, which shows Saint

Michael appearing in a textile workshop, the obraje

workers wear far more humble clothing than does the

overseer at center, suggesting how in Spanish American

art distinctions of wealth and modes of labor could

be registered. Obrajes—or

factories, largely for the production of textiles—also

benefited from social segregation and debt peonage.

They were staffed with hundreds of indigenous, mestizo,

and mulatto workers. Women, who were usually banned

from guild workshops except as family members, could

also find work in obrajes. While laws required that

they be paid for their work, many obraje workers found

themselves weaving and spinning in servitude, using

their labor to pay off debts that could take years

to erase. Even in this painting, which shows Saint

Michael appearing in a textile workshop, the obraje

workers wear far more humble clothing than does the

overseer at center, suggesting how in Spanish American

art distinctions of wealth and modes of labor could

be registered.

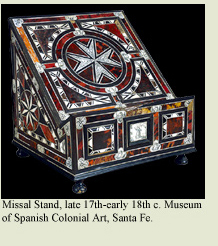

Trade,

as much as labor, also shaped the making of artworks

and daily objects. Raw materials that could be cast,

woven, sculpted, and painted were abundant in Spanish

America, yet imports from Asia and Europe also played

a leading role. At times, imported materials were

incorporated into colonial art works as in statues

of saints with hands and faces carved of ivory from

Asia. In other instances, artists and craftsmen took

ideas and inspiration from foreign practices. For

example, both the famous blue-and-white pottery from

Puebla and this missal stand, inlaid with bone and

tortoise shell, combined European and Asian styles

and techniques. The artisans of Spanish America may

not have been well traveled but they nevertheless

participated in the world trade networks taking form

in early modernity. Trade,

as much as labor, also shaped the making of artworks

and daily objects. Raw materials that could be cast,

woven, sculpted, and painted were abundant in Spanish

America, yet imports from Asia and Europe also played

a leading role. At times, imported materials were

incorporated into colonial art works as in statues

of saints with hands and faces carved of ivory from

Asia. In other instances, artists and craftsmen took

ideas and inspiration from foreign practices. For

example, both the famous blue-and-white pottery from

Puebla and this missal stand, inlaid with bone and

tortoise shell, combined European and Asian styles

and techniques. The artisans of Spanish America may

not have been well traveled but they nevertheless

participated in the world trade networks taking form

in early modernity.

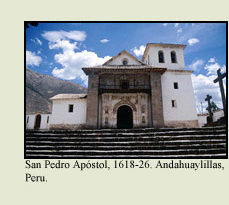

Outside

cities, small communities called upon local artisans

to make the structures and works they needed. Images

were made for display in parades and public buildings;

churches, such as this one in Andahuaylillas, were

raised and typically decorated by local carpenters,

masons and painters. While not viewed as artful by

metropolitan standards, provincial works served an

important set of audiences and purposes. And they

were no less effective than the most elaborate retablos

of Lima in honoring the saints, evoking the Last Judgment,

or recalling ancient history. While many of the names

of provincial and indigenous painters and other craftsmen

are no longer known, their images remain, testifying

to the extraordinary creative abilities and intense

desire for images that flourished beyond the guilds

and their world of official “good taste.” Outside

cities, small communities called upon local artisans

to make the structures and works they needed. Images

were made for display in parades and public buildings;

churches, such as this one in Andahuaylillas, were

raised and typically decorated by local carpenters,

masons and painters. While not viewed as artful by

metropolitan standards, provincial works served an

important set of audiences and purposes. And they

were no less effective than the most elaborate retablos

of Lima in honoring the saints, evoking the Last Judgment,

or recalling ancient history. While many of the names

of provincial and indigenous painters and other craftsmen

are no longer known, their images remain, testifying

to the extraordinary creative abilities and intense

desire for images that flourished beyond the guilds

and their world of official “good taste.”

When

the mechanics of the art and craft production in Spanish

America is considered from today’s perspective,

it seems familiar and strange, tragic and wonderful.

Familiar, in that many of the same art industries

are found today in Latin America. Potters, silver

workers, textile makers continue to supply beautiful

goods for both local and international markets. Strange,

in the primacy of skill over innovation, and the dependence

of artists upon the wants of patrons. Tragic, in the

endemic use of poorly paid or forced labor, and the

wide scale loss of pre-Columbian art-making traditions.

And wonderful in that, despite the many flaws of the

system, works of extraordinary inventiveness and skill

have survived to the present day. When

the mechanics of the art and craft production in Spanish

America is considered from today’s perspective,

it seems familiar and strange, tragic and wonderful.

Familiar, in that many of the same art industries

are found today in Latin America. Potters, silver

workers, textile makers continue to supply beautiful

goods for both local and international markets. Strange,

in the primacy of skill over innovation, and the dependence

of artists upon the wants of patrons. Tragic, in the

endemic use of poorly paid or forced labor, and the

wide scale loss of pre-Columbian art-making traditions.

And wonderful in that, despite the many flaws of the

system, works of extraordinary inventiveness and skill

have survived to the present day.

|