Learning to ‘Be Navy’

Campus Life

Published June 11, 2019

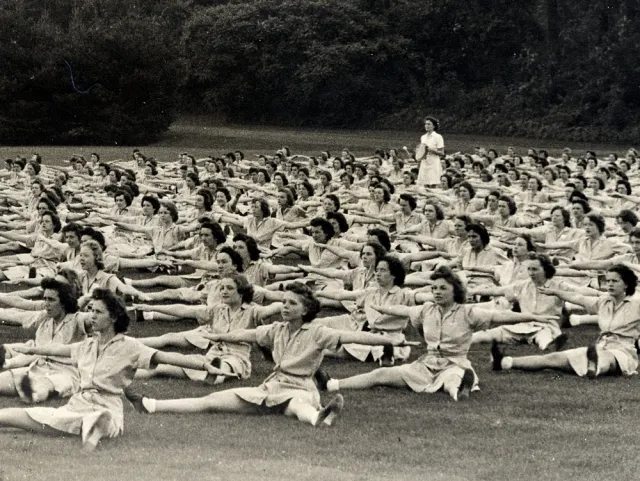

During World War II, the campus transformed itself into U.S.S. Northampton, the official training ground for the country’s first women naval officers. The WAVES moved into student houses, did calisthenics on the playing fields and took over the Alumnae House. Here’s a look back at how Smith made military history.

World War II military buildup meant that women were needed to serve. Congressional legislation created a women’s Navy Reserve, and the Smith campus was the training ground. Between 1942 and 1945, thousands of enlisted women came to Northampton to become officers in the U.S. Navy.

USS Northampton

Their uniforms weren't even ready when the Navy’s first women officer recruits arrived in Northampton on August 28, 1942. But their hair was uniformly short, carefully curled and pinned so as not to cover their collars, and the heels of their black oxfords measured between 1 and 1.5 inches. Of the 150 women in this pioneering class, eight were Smith alumnae. All were highly educated and had civilian work experience that would benefit the Navy. They were among 9,000 women—and 200 Smith alumnae—who, over the course of the next two and a half years, would train to become U.S. Navy officers. And the Smith campus would be their staging ground.

The recruits’ arrival turned the campus upside down as they moved into student houses, practiced drills on the playing fields and turned the newly built Alumnae House into their headquarters. Still, few on the Smith campus today know anything about the college’s historic role in preparing women officers to “be Navy” at a time when the country needed every able-bodied person to join the war effort.

In the months following America’s entry into World War II—triggered by the Japanese attack on the U.S. Naval Base in Pearl Harbor in December 1941—Congress passed legislation creating a Women’s Reserve of the Navy. Women who enlisted would come to be known as WAVES, or Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service.

The idea of women serving in the military was not entirely unprecedented. In World War I, 13,000 women had served as yeomen in the Navy, and the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) had been established in May 1942. Still, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox was uniquely ambitious in pushing for women to serve as regular members of the Navy rather than as auxiliary civilian employees. The WAVES, he declared, would be in, not with, the Navy, with all the privileges and responsibilities this entailed.

It was not an easy endeavor. Memoirs, newspapers and even the Congressional Record give a sense of the public’s animosity toward the idea; many were convinced that “good girls” didn’t join the military, only man chasers, tomboys or lesbians. Knox’s success was due in large part to his alliance with the Seven Sisters. Early on, the Navy had created a Women’s Advisory Council, composed of 12 prominent women in the field of education, including Radcliffe College President Ada Comstock 1897 and Barnard President Virginia Gildersleeve. Mildred McAfee, president of Wellesley, was named the first director of the WAVES.

Members of the advisory council were annoyed that their principal suggestion—more pockets—was ignored.

While none of these women had a naval background, the Navy trusted their impeccable reputations and their experience in educating women. They advised the Navy on how to attract the “right” type of applicant, how to adjust Navy housing for women’s comfort and how to discipline women without being too harsh or too gentle. The council also worked with the Mainbocher fashion house, designing uniforms that would be both functional and stylish. The resulting blue serge suits were featured prominently in WAVES recruitment efforts, although members of the advisory council were annoyed that their principal suggestion—more pockets—was ignored.

The selection of Smith as a training site for officers was also due to the council’s influence. Elizabeth Reynard, a Barnard professor, became one of the first female commissioned lieutenants and was tasked with choosing a location for the training school. Vassar and Smith were among the finalists. Both, she said, were safe campuses, conveniently located and with stellar reputations that would attract Navy recruits. When Smith President Herbert Davis realized that the small dining facilities in the Smith houses would struggle to accommodate the number of WAVES, he persuaded the Hotel Northampton to join the cause. Reynard was impressed by Davis’ eagerness to assist in the war effort, and that settled it: The WAVES were coming to Northampton.

In the summer of 1942, Smith’s campus was transformed. Signs went up above the Alumnae House: UNITED STATES NAVAL RESERVE MIDSHIPMEN’S SCHOOL. The beds in Capen, Northrop and Gillett (and all the rooms in the Hotel Northampton) were replaced with bunk beds. The dining halls were likewise emptied and equipped with desks and blackboards; additional classrooms were reserved in Faunce Hall (now the Davis Center) and Seelye. The outfitting of what would become known as U.S.S. Northampton was complete.

The first to arrive were staff members, who settled into the Alumnae House. Captain Herbert Underwood, a World War I veteran and recipient of the Navy Cross, came out of retirement to serve as the commanding officer, with newly commissioned Lt. Elizabeth Crandall as the ranking woman officer. The remaining 80 staff officers and instructors were all men.

Navy training for officers was not called boot camp, but was dubbed “indoctrination”—a Navy term that, director Mildred McAfee admitted, “made [me] shudder.” Women arrived as seamen and, after a month’s successful indoctrination, graduated to midshipmen. Midshipmen’s training was initially designed to last an additional three months. The women trainees, however, “proved smarter than expected,” and on Underwood’s recommendation, their training was shortened first to two months, and then to one. Upon completing the training, women were commissioned as either ensigns or lieutenants junior grade, depending on their performance and their civilian work experience. Some remained at Smith for advanced communication training or went on to advanced training in supplies and accounts, radio communication or engineering. Others were sent directly to Navy bases and recruiting offices across the continental United States.

Some remained at Smith for advanced communication training. Hear from these code-breakers in “Smith’s Hidden Weapon.”

Course of Study

During indoctrination, a midshipman’s day was scheduled to the minute. If she lived on campus, she woke at 0620 every day except Sunday. She had 40 minutes to dress, make her bed and help her roommates clean. On Saturdays, staff officers would inspect the rooms for cleanliness. At 0700, the campus battalion marched down Main Street, in formation, to the Hotel Northampton for breakfast. By 0750, the entire group was again in formation and marching back to Smith for instruction. Four days a week, the WAVES attended five courses, a group lecture and two hours of exercise drills. They had two hours and 45 minutes of study hall each day and two hours of liberty. Sunday was the only true rest day.

The WAVES found the course of study as challenging and comprehensive as college courses, but compressed into a much shorter time. Midshipman Helen Clifford Gunter later wrote in her memoir Navy Wave that she was baffled by the difficulty of her final exams. But she was cheered by a rumor that the Navy had deliberately made the WAVES’ exams harder because early classes of women had scored higher than the male officer candidates at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. The WAVES, it seems, were supposed to relieve men for sea duty, not show them up.

For all this intensive study, the most important function of the Naval Reserve Midshipman’s School was teaching women how to “be Navy.” The WAVES were not civilians playing dress-up in military uniforms; they were full-fledged members of the military. They learned Navy lingo and etiquette. They sat through the same classes as men, including lessons on how to recognize enemy aircraft and how to organize a crew while afloat. They memorized the Navy’s regulations and lived by its discipline.

Mildred McAfee noted the WAVES’ enthusiasm. “Whenever girls get together, somebody starts a [news]paper; somebody is apt to organize a glee club … teams for all kinds of games spring into existence,” she observed, and the WAVES of Northampton were no exception. They wrote dozens of songs and parodies about Navy life and put on a number of short plays and musicals, both to entertain themselves and to raise money for the purchase of war bonds.

Sounding Off!

The most ambitious cultural product of the midshipmen was Sounding Off!, a weekly newspaper that documented women’s adjustment to Navy life. “Midshipman Becomes Citizen in September, WAVE in November,” Sounding Off! wrote of a refugee from fascist Spain. The first Puerto Rican WAVE and the first Korean WAVE were profiled, as were women who had followed their fathers or brothers into the Navy. One midshipman joked that her enlistment had greatly offended her mother, a Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps officer.

Sounding Off! was careful to avoid topics that could be controversial, however. For instance, WAVES did not receive benefits equal to those of their male counterparts or serve overseas; they were advised not to pursue postwar naval careers. Women’s complaints about these limitations did not appear in print. Also unreported was the fact that African American women were excluded from serving as officers. The Navy restricted black men to enlisted ranks for much of the war, and thus argued that there was no need for black officers in the WAVES. The policy was protested by the NAACP, the National Council of Negro Women and, privately, by McAfee and many members of the Women’s Advisory Council. Eventually, the policy was rescinded, and the first two female African American officers arrived at the U.S.S. Northampton in the fall of 1944, including Harriet Pickens, a member of the Smith class of 1930.

Sounding Off! and Smith College Associated News (SCAN), the college newspaper, also documented the relationships between WAVES and Smithies. Soon after the WAVES’ arrival, a letter to the editor signed “Three Indignant Members of Staff” scolded Smith students for their treatment of the WAVES, claiming that students had jeered and giggled as they passed. The story was picked up by the Associated Press, much to the consternation of both Smith and the Navy. Students, WAVES and staff from both institutions quickly refuted it. In a later issue, SCAN interviewed three midshipmen who were recent Smith graduates. “The prevailing opinion was that the story was definitely untrue,” SCAN reported. “One declared, however, that seeing her friends stare at her as she marched by was somewhat uncomfortable.”

Overall, the relationship between students and midshipmen was one of “mutual esteem,” according to Lt. Cmdr. Margaret Disert. Students tied red, white and blue ribbons to the handlebars of their bikes to indicate that footsore WAVES could borrow them during their rare hours of weekend liberty, as most had not brought cars to campus. WAVES were often invited to house teas or outings. President Davis spoke at a WAVES commencement and Director McAfee at a Smith Commencement.

In February 1945, as the ratio of officers to enlisted women was growing too high, the training school in Northampton closed. When the war ended soon after, the college returned to its regular routine. Wiggins Tavern, open to the public once more, was mobbed by Smith students who walked down Main Street in small groups rather than marching in formation. Capen, Northrop and Gillett housed Smith students again. The “Naval Reserve Midshipmen’s School” signs were taken down from the Alumnae House and Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal installed a plaque beside the door, commending Smith for its cooperation.

The WAVES had already departed, but the final issue of Sounding Off! recorded their fond farewell: “For the staff of the U.S.S. Northampton, skippered by Capt. Herbert W. Underwood, USN (Ret.), during its entire cruise, today means the end of a happy tour of duty.”

Want to learn more? Follow this description of her research by Alex Asal ’16.

Summer 2019 Smith Alumnae Quarterly

Alex Asal ’16 received her master’s in history with a certificate in public history from the University of Massachusetts. She is a tour guide at the Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site in Philadelphia.

Images courtesy of Smith College Special Collections