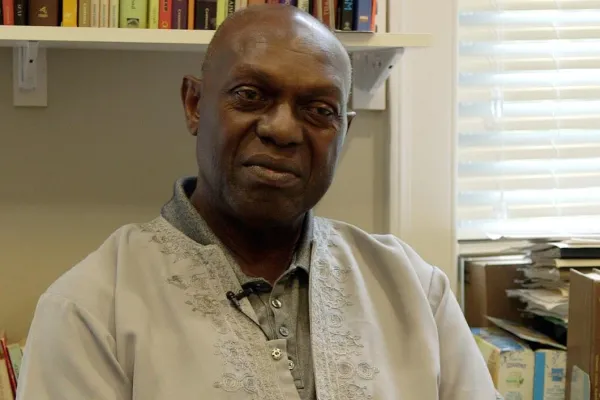

Linking the Old and New Jim Crow: Professor Al Mosley’s Latest Scholarship

Research & Inquiry

Published March 1, 2017

If he had not found philosophy as a specialized academic pursuit, Albert Mosley might have taken a detour onto the highway of jazz and blues that passed through Nashville in the ’60s.

Indeed as a young college student in Tennessee, he spent his off hours playing alongside the likes of Count Basie and Ray Charles—who liked the way the young trumpet player from Dyersburg hit the high notes and often called on him to join jam sessions at local clubs.

“College or music? I was still improvising with my life, with whatever came up,” he says. So when his parents and an older brother convinced him to leave Tennessee and continue his college studies up North after his sophomore year, he agreed.

Today the disparate roads that Mosley has traveled in life merge in his academic work. As a professor of philosophy at Smith College, he draws on his scholarly insight and unique experiences to enrich the culture on campus. Despite his accomplishments, he admits that, as a black man, he still harbors a fear of racial assault and arrest, which has deep roots in his own upbringing in a sharply segregated Jim Crow South.

In his new paper, “Narratives on the Ethics of Living Jim Crow” —delivered at Emory University in fall 2016 at the California Roundtable on the Philosophy of Race—he uses the analytical roots of the work of contemporary philosophers and writers and his own personal narratives to illustrate how the threat of violence was used to humiliate, subordinate and exploit blacks and the poor in the Jim Crow South. “Jim Crow was the American version of white supremacy. It was a hierarchical worldview in which men were superior to women, Europeans were superior to non-Europeans and Aryan Europeans were superior to non-Aryan Europeans.”

Now, current events—including the shootings of black men and police officers, the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, and the mass incarceration of the black population—have led him down another avenue. He has chosen to examine the issues and place them in historical context to better understand the link between the old and new Jim Crow.

More personally, Mosley chronicles the details of his own upbringing as he strives to create a narrative structure that reflects the richness, diversity and struggles of black American life.

“I entered Tennessee State University in 1958 in Nashville; it was where most of the people I knew went to college, if they went at all. Black people were not admitted to the major universities in Tennessee, such as the University of Tennessee and Vanderbilt.”

In his junior year, Mosley transferred to the University of Wisconsin in Madison, which had an overwhelmingly white student body. With a familiar determination and curiosity, he finished up his undergraduate studies in mathematics in 1963 and entered a doctoral program in philosophy, focusing on the philosophy of mathematics and science. Other developments contributed to the narrative fabric of his life at the time: the civil rights movement and the university’s increasingly radical Madison campus.

“I had been segregated from whites all my life, and I was curious about them. I wanted to understand why they were so special, what gave them so much power and privilege. Wisconsin gave me the opportunity to see that not all white people were racist. Most of the people I encountered there opposed the injustices suffered by black people and extended themselves on my behalf. …There were lots of discussions and demonstrations in favor of the U.S. civil rights movement and the liberation of colonized people in Africa, Asia and South America. Oppressed people were showing their emergent strength.”

He continued to seek out unique academic experiences. With a fellowship to study the history and philosophy of science at Oxford in 1967, Mosley’s interest in the civil rights struggle in the U.S. expanded to include the struggles of oppressed people all over the world.

In just a few decades, every fixed notion about racism and white supremacy that had oriented Mosley to the world had begun to expand. As a philosopher and musician, thinker and professor, Mosley knows there is much work to do, and he continues to contribute to what he considers to be the rightful involvement of philosophy, “both emphatically and analytically, with the legacy of Jim Crow.”