The Perks of Having a ‘Weird’ Brain

Smith Quarterly

Author Sadie Dingfelder ’01 on the origins of her new book

Illustration by Dror Cohen

Published October 11, 2024

I had very few friends in middle school, so when one of them went missing, I was bereft. In those pre-internet days, I just assumed she had moved away. It would be decades before I figured out what had happened: She had cut her hair—which, in my eyes, turned her into a stranger. Day after day, I accidentally snubbed her, and my former friend responded in kind.

In 2019, I discovered that I am faceblind—and always have been. This neurological disorder is known as prosopagnosia, and it means that everyone looks pretty much the same to me. When I wrote about it for The Washington Post, where I worked at the time, people started coming out of the woodwork, telling me stories about myself that were both hilarious and heartbreaking. Suddenly, a lifetime of loneliness and missed connections made a lot more sense.

As I worked on the article with my editor, I cried. A lot. And no one cries at The Washington Post! All around me, other reporters were stoically dealing with real tragedies while I was sobbing for the 14-year-old version of myself. I felt ridiculous, and I was so relieved when the story finally ran. “I’m never doing that again,” I told my husband, Steve. “From now on, I’m only writing about other people.”

I kept that promise for about a year. But after being laid off and then trapped in a tiny apartment because of the pandemic, my idle mind kept coming back to the same question: Why am I faceblind? Prosopagnosia is largely genetic, but my family of politicians and Rotary Club presidents tends to be exceptionally good at face recognition. So, what the heck happened to me?

As I did all the usual pandemic things—baking bread, learning TikTok dances—I couldn’t stop thinking about this question. One day, I army-crawled past my husband (to avoid making a pantsless cameo on his Zoom meeting) and disinterred a bag of studies that I’d stashed in the back of a closet.

I sat in that closet, in my underwear, for hours. The more I read, the more I began to realize that prosopagnosia is just the tip of my neurodivergence iceberg. At age 40, I thought I knew myself. I was so very wrong.

The smoking gun was a 2012 study which found that kids with both amblyopia and strabismus—also known as lazy eye—are in for a lifetime of face-recognition issues. Like many kids, I had surgeries to “fix” my misaligned eyes. But the underlying neurological problem remained: My brain never learned to integrate information from my two eyes into a single 3D image. As a result, I am stereoblind. And I always have been.

Once again, I found myself reevaluating my entire life story. No wonder I hate ball sports! No wonder I was always too scared to learn to drive! If you could beam into my head, you’d find my world to be very, very flat. People who have learned to see in 3D as adults describe seeing familiar objects inflate before their eyes. Hung coats take on the depth and richness of paintings by Dutch masters; trees become living sculptures; the spaces between things become almost palpable. The more I read, the more I wanted that experience for myself.

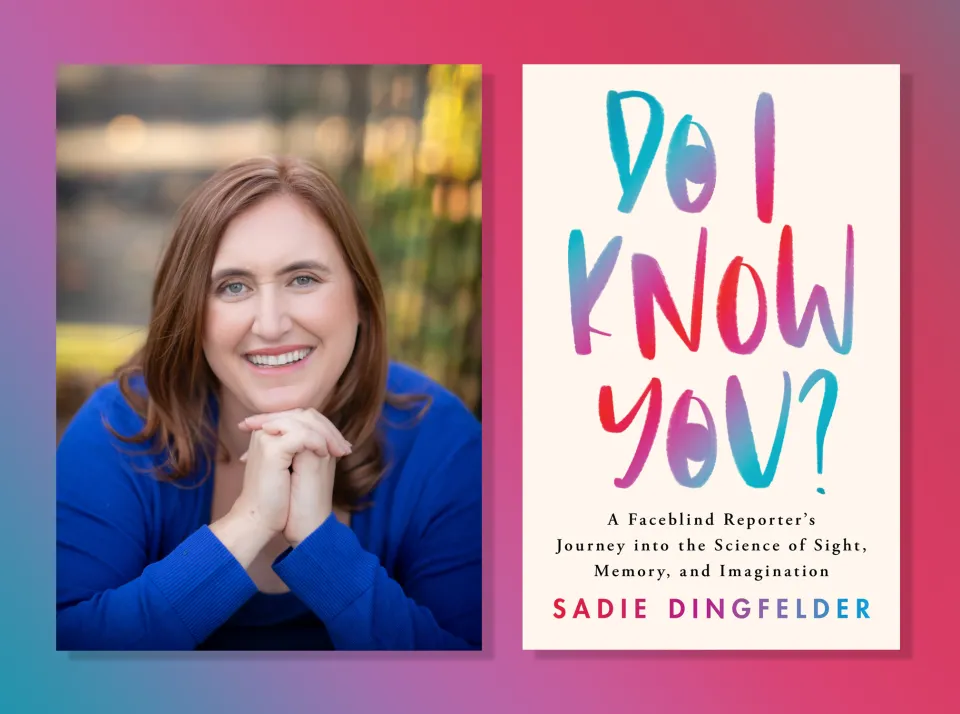

Sadie Dingfelder ’01 and her new book, Do I Know You? A Faceblind Reporter’s Journey Into the Science of Sight, Memory, and Imagination (Little, Brown Spark, June 2024).

Photo by Oxana Ware

As I began looking for studies to join, it occurred to me that I was having quite the nerdy midlife crisis. It also occurred to me that my weird brain might actually be a gift. I’m a science writer, and my own personal cortex was turning out to be quite interesting. I began emailing neuroscientists and taking online screenings, and the study invitations began rolling in. Scientists at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the University of Toronto all wanted to scan my brain. The invitation I was most excited about came from California. Scientists at Berkeley wanted me to try a not-yet-FDA-approved, virtual reality–based treatment for stereoblindness.

How was I going to pay for all that travel? With some reluctance, I lifted the writing-about-myself ban. I got myself an agent—Dara Kaye ’09—wrote a 100-page book proposal, and landed a book deal. It took another two years before my nerdy midlife crisis took corporeal form: a 304-page book called Do I Know You? A Faceblind Reporter’s Journey into the Science of Sight, Memory, and Imagination.

“At age 40, I thought I knew myself. I was so very wrong.”

In the course of writing my memoir/popular-science mashup, I’ve learned a lot about myself, but also about neurodivergence in general. I’m increasingly convinced that all of our current categories are garbage, and diagnoses like autism and ADHD are soon going to sound as vague and old-timey as having the vapors. I’ve also learned that, after ignoring the question of subjective experience for more than a century, scientists are beginning to come up with clever new ways to verify, disprove, or at least triangulate what we claim is going on inside our heads. And they are finding that there are a lot more flavors of human consciousness than anyone ever realized.

I now know that, in addition to my perceptual differences, my inner life is quite unusual. I can’t visualize, I have no inner monologue, and I can’t relive important moments from my past. This sounds like a litany of deficiencies, but I’ve come to appreciate my weird brain. I see the world differently from other people—literally and figuratively—and my perspective is valuable because it’s so rare. I’ve learned to embrace the peculiarities of my brain because they’re what make me me. It’s not always easy to live in a world built for and by brains that are quite different from your own, but at least it’s never boring!