The Power of the Printed Page Endures

Research & Inquiry

Published April 1, 2012

In a landscape teeming with laptops, iPads, iPods, Kindles and Nooks, where does something as seemingly old-fashioned as the ink-and-paper book fit in? Does it have a viable future?

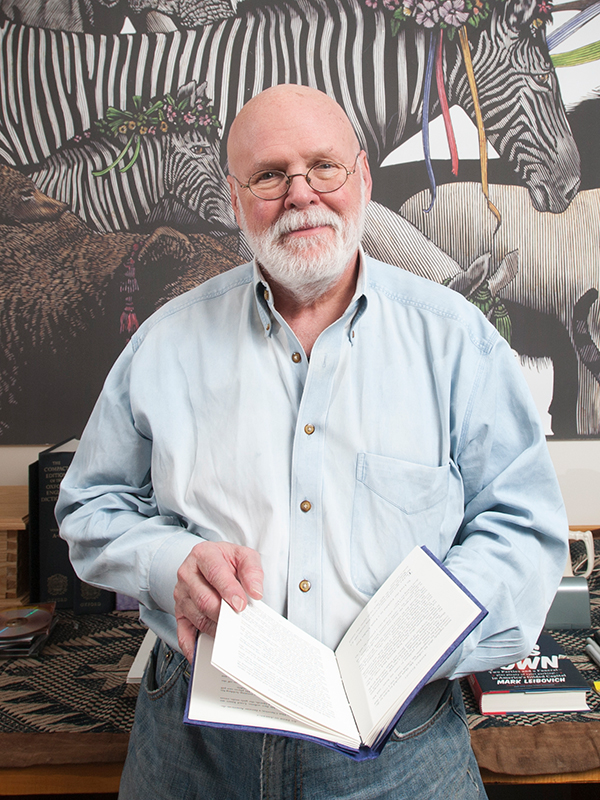

Ask these questions of Barry Moser, acclaimed book artist, illustrator and printer to the college, and he’ll point to dozens of examples from history when new technologies and innovations threatened the printed book’s existence—yet still it prevailed, fundamentally intact. “People like me who have been in the business of building books for a long time, we’re seeing this new technology come along and we don’t know what to do with it yet,” he says. “But we will figure it out.”

Barry Moser

Barry Moser

A traditionalist at heart, Moser is confident that the book as we’ve come to know it isn’t going anywhere fast. Rather it will adapt to the technologies of the times while maintaining its essence as a printed piece—and piece of art, much as it has throughout history.

Take, for example, the evolution from handwritten books to the invention of the printing press and movable type by Johannes Gutenberg. The process of creating books changed in light of the new, more modern machinery, but the end product remained largely the same. “Gutenberg’s invention of casting type was to make something like what was already in existence—handwritten type,” Moser says. He believes that something similar will probably happen here.

Convenience fuels the popularity of wireless devices like the iPad and Kindle —which fulfill all of your media needs (music, movies, books, the Internet) on a portable seven-inch screen, literally at your fingertips. And consumers are eating these up. During the holidays, for example, Amazon announced that it was selling more than a million Kindles a week. Apple has set sales records with its iPad, and, according to Publishers Weekly, e-book sales rose almost 40 percent in 2010; meanwhile sales of mass-market paperbacks fell in 2009 and 2010 by more than 13 percent.

Though Moser can appreciate the ease and immediacy made possible by new technologies, he suggests that much gets lost when our experience with great literature boils down to simply touching a screen. “If you’re going to present some major work of literature, it should have a form that more or less equates the importance of the document itself,” he says. “I just can’t imagine that reading Don Quixote on a television screen is nearly as exciting or as pleasurable as reading it [by] turning the pages.”

Moser appreciates the way ink is absorbed on the printed page, how typography is used in juxtaposition to imagery and the impact of great photography—all qualities that are difficult to replicate on an electronic device, he says.

As a book artist who has illustrated a variety of works from Lewis Carroll’s Alice: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to the Holy Bible, Moser is particularly enamored of the way ink is absorbed on the printed page, how typography is used in juxtaposition to imagery and the impact of great photography—all qualities that are difficult to replicate on an electronic device. “If you were to bring up a reproduction of John James Audubon’s Birds of America on a Kindle, it’s [seven inches], and the original is an elephant folio—it’s about 30 inches. You can never do that on a Kindle, you’ll never be able to see the physical presence,” he says. “There are certain things that require majesty. And a Kindle ain’t never gonna be majestic.”

That’s not to say that a new generation of book lovers won’t be able to marry tradition and innovation in the next phase of book design. “Younger people coming on who were basically born with a mouse in their hand and who are in love with fine typography and so forth, they’re going to figure this out,” Moser says. “I’ll be gone by the time that happens and that’s fine.”

“I think eventually we’ll find that the technology is merely a tool, another tool,” he adds. “And I don’t think it’s a tool that’s going to replace books.”

Sidebar: Archivists Consider New Ways to Preserve for the Future

What does the digital future hold for library archives and the preservation of ink-and-paper collections?

Over the past few decades, the introduction of digital media has dramatically changed the contents of archives and increased the availability of materials; yet the older paper files of previous generations still hold their appeal. And preserving all of these new and old materials presents challenges for archivists.

In addition to housing paper resources, the Smith College Archives holdings now include CDs, DVDs, floppy disks and diskettes, reflecting the rapid changes in record-keeping technology over the past few decades. Converting these, and scanning some of the paper holdings, to similar digital file formats would make them more easily available. It also means that researchers would be able to review these records electronically over the Internet, so interested parties would not have to physically come to the archives.

The College Archives houses a rich collection of materials documenting the history of Smith College from the 1860s to the present.

Yet digital records, although obviously different from their paper counterparts, still present similar preservation problems for archivists. Water damage or insects, for example, could ravage through a box of paper in the same way that viruses or incompatible technology could destroy the contents of a disk or hard drive. Thinking ahead to properly save files in a way that they can’t be corrupted expands the job of archiving; it is now the responsibility not only of historians but also of those of us who keep personal records.

Smith Archivist Nanci Young explains the modern archivists’ plight. “Helping to make people more aware of the issues at the point of creation is now an important part of our jobs, rather than waiting for boxes of paper to come in. If we don't talk to people about their digital [content] at the beginning, there may not be anything at the end to come to the archives!”

Barry Moser illustrates this point in reminiscing about his first computer. “The first machine that I owned, a Mac 2, had a black screen with green bitmap letters. It printed out bitmap on a constant feed sheet.” Twenty years later, the programs used by that computer no longer exist. He explains, “The correspondence I wrote on that machine, unless somebody has some universal recovery program, all of that’s gone.”

But paper records hold benefits far beyond their permanence. The unique opportunity that students have at the archives to read actual letters can evoke a reaction of astonishment.

“We see this when undergraduates ‘oooh’ and ‘ahhh' over holding a letter in their hands that was written by a student who graduated in 1879,” explains Young. “There is something about the tactile nature of early handwritten letters that fuels genuine excitement.”

As the technology advances, it is likely that systems of digital preservation and storage will become more uniform and comprehensive. Electronic sources may soon provide the same level of stability and security that only paper records once could.

“A box of paper can sit on a shelf and, if we don't have fires or floods, it will probably be okay in 100 years, even if we never open it again,” says Young. “We know that's not the same for digital materials that require certain software and hardware and are fragile and temperamental. It is certainly easier to share certain kinds of digital information quickly, but whether we can truly preserve for long-term access is the big question.”

Savoring the Book With a Concentration of Study

For a new generation of book lovers and scholars, Smith offers the concentration in book studies, which connects students with the exceptional resources of the Mortimer Rare Book Room and the wealth of book artists and craftspeople of the Pioneer Valley.

Through classroom study, field projects and independent research, students in this concentration learn about the history, art and technology of the “book”—which has been broadly defined to extend from oral memory to papyrus scrolls to manuscripts, printed books and digital media. Book studies concentrators design capstone projects in a wide variety of areas that include medieval manuscripts, early and fine printing, book illustration, children’s picture books, the book trade, artists’ books, censorship, the history of publishing, the secrets of today’s bestsellers, the social history of books and literacy, the history of libraries and book collecting, and the effects of the current digital revolution on the material book.

For more information go to www.smith.edu/bookstudies.