Shake It Up

Campus Life

Small earthquake energizes Smith geoscientists

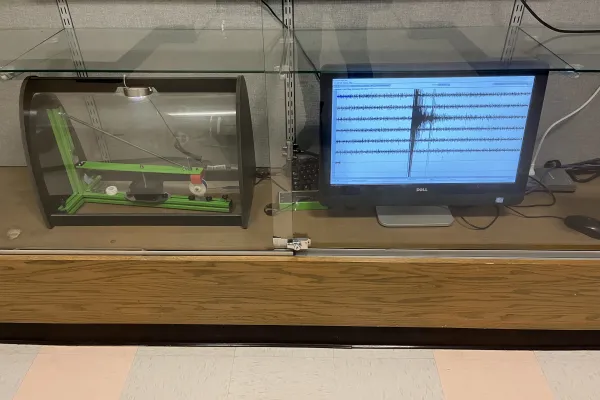

A seismometer and seismograph in the Smith College Department of Geosciences show the signal from the Friday morning earthquake.

Published April 5, 2024

Professor of Geosciences Amy Rhodes was leading a discussion on stream water pollution when her students’ phones began to buzz. Just moments before, a 4.8 magnitude earthquake centered in New Jersey had shaken much of the Northeast. Had anyone felt it?

Students in her class had not. “I'd like to think it was because they were so focused on the discussion article,” said Rhodes, ”but more likely it was too faint for us to feel.”

When class ended, a group rushed down the hall to check the geoscience department’s seismograph. The sensitive instrument confirmed the story: A huge uptick in shockwaves indicating earthquake activity.

“We rarely hear news about earthquakes occurring here, certainly ones that we can feel, so it was an energizing moment for everyone in the geosciences department,” said geosciences major Claire Anton ’25, adding that she was bummed not to feel anything at the time.

Liliana Hetherman ’25 was in her house when the tremor began. The earthquake caught her off guard. “I was just lying in my bed and all of a sudden my room walls started rumbling. I thought my house was either collapsing or they were drilling for construction—and then my mom called me.”

In New York City, close to the epicenter, Hetherman’s family had just felt the full force of the quake.

Like others in Sabin-Reed, Professor of Geosciences Jack Loveless didn't feel the earthquake himself, but said he heard reports of students who did elsewhere on campus, especially along Elm Street. Loveless, whose research focuses on plate tectonics and earthquake cycles, said the difference in those who felt the quake or not was likely related to the ground below.

"The thickness of sediment beneath buildings can influence the intensity of shaking," he said, "and so different parts of campus may be more likely than others to feel earthquakes. The event seemed widely felt by my neighbors along South Street in Northampton, which is built on thick sediment."

Loveless noted that although Northampton itself is far from an active tectonic plate boundary, the eastern U.S. has an ancient tectonic history, dating back to the formation of the Appalachian Mountains. Every so often these ancient faults get squeezed and stressed enough to generate an earthquake.

"Thankfully this is a pretty rare occurrence," he said, adding that an event like today is "good motivation for people to learn about earthquakes and how to respond (drop down under a sturdy piece of furniture, cover your head and neck, and hold on)."

Rhodes said students in her introductory geology classes are often surprised to hear how many earthquakes occur around the world. “Most of these happen along plate boundaries and go unnoticed because they are either small or occur away from populated areas,” she said, adding that earthquakes in populated areas, such as this morning’s, are less frequent. Rarer still are the large earthquakes, such as the recent 7.4 magnitude quake near Taiwan, which can be both damaging and frightening.

“The rarity of feeling earthquakes here in Massachusetts makes today novel and creates a lot of excitement, particularly knowing that it was not a large earthquake that would have caused widespread damage,” said Rhodes. “Events like these remind us that the Earth is very active.”

Pictured: A seismometer and seismograph in the Smith College Department of Geosciences show the signal from the Friday morning earthquake.