Why Some Answer the Call to Activism

Faculty

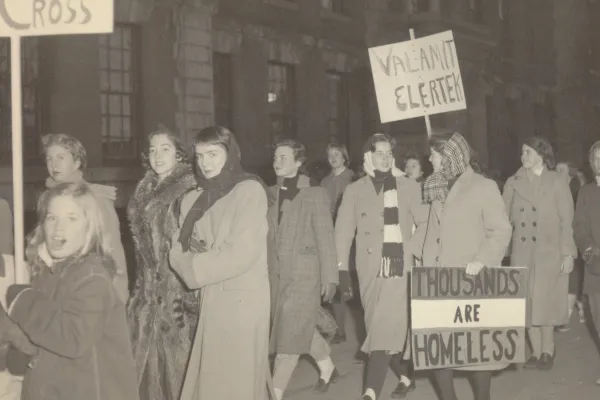

Smith students march in support of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Photograph courtesy of Smith College Special Collections

Published July 18, 2024

Whether advocating for women’s right to vote, marching against the war in Vietnam, standing against apartheid, or fighting for reproductive justice, Smith students have a long history of social activism. This past year saw efforts by students to rename campus buildings and push for the college to divest its endowment of defense-related funds. In February, the former Wilder House was renamed Haynes House after students and other community members raised concerns about the Wilders’ advocacy of eugenics and excavation of Native American human remains for the purpose of research and teaching. Then, in the spring, a group of students occupied College Hall in the midst of national protests related to the Israel–Hamas war. The occupation ended peacefully after less than two weeks.

Professor Lauren Duncan studies the psychology of activism. In this conversation, she reflects on what inspires activism, whether we’re reaching protest fatigue, and why the act of renaming buildings can potentially improve students’ well-being.

In a nutshell, what is your research into activism about?

Simply, I study why some people want to change society and why others want to keep it the same.

And what have you discovered? What moves people to become politically active?

Not surprisingly, activism comes from a sense of injustice. Basically, you begin to identify with a social group—usually race, gender, sexual orientation, etc.— and believe that what happens to that group will also affect you. Then there is a sense that your group is unfairly deprived of power and resources, and you blame the system rather than the individual. With that comes the sense that you need to organize collectively to change things, that doing something on your own isn’t going to make a big difference.

Was there something specific that sparked your interest in activism?

My family is very conservative, and I’m not. From childhood, I was always interested in why I think differently than the rest of my family members. Where did this come from? When I was an undergraduate, I majored in economics and thought that I should go into business. I did end up working for an economic consulting firm after I graduated, but then later I began exploring psychology and gender because my family was very sexist. My adviser at the University of Michigan happened to be the chair of women’s studies, so I had to take women’s studies classes; that was life-changing for me. I hadn’t encountered feminism before that. Eventually, I started looking into conservative and liberal ideology and activism. It all really does stem from me just trying to understand my own family situation.

Holidays must be interesting. What does your family think of your work?

We have a family text chain. Sometimes that can get pretty intense. I was recently interviewed by an NBC reporter about protest fatigue, and when the interview aired I texted the link to my family. My nieces and nephews were like, “Great job, Auntie Lauren!” But then a couple of my brothers were jumping in with their rabid conservative views, saying things like, “All pro- testers should be thrown in jail.” Stuff like that. So, it can be difficult and a bit challenging sometimes. But the great thing about text chains is that you can mute them.

Still, given all that’s happening in the world today, it must be an exciting time to be studying activism.

In many ways, it is. What I think is particularly interesting is the ubiquity of social media and the internet, its increased polarization, and how it is being used both for good and for bad. Things are definitely different than they were when people were studying the large-scale social movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Social media can connect communities that otherwise would have no way of connecting and expose people to ideas and movements they might otherwise never encounter. I recently told students in my Political Psychology class how I did some interviews with Italian feminist activists in 2018 and 2019. One woman told me how she came from this remote little place in Italy, and so I asked her how she came into contact with feminism. She said through the riot grrrls of the ’90s and watching Agent Scully on The X-Files. But then, of course, you have groups like the incels. You get these men who hate women and they’re able to band together over the internet and promote these horrible, disturbing ideas.

Going back to the idea of protest fatigue, do you think we’re reaching that point?

Some of that has to do with the 24/7 nature of news cycles and what we’re exposed to through the media. That can feel overwhelming. But at the same time, there are so many protests about so many things because people are trying to get their voices heard. It can be exhausting, both for the protesters and for those of us watching. These are reactionary times, though, and I think it’s really good that people are protesting.

As someone who studies activism, what was your reaction to the recent spate of student activism here at Smith, particularly the occupation of College Hall this spring and the renaming of the former Wilder House?

Well, it’s normal, and it’s actually normal developmentally too. College students, at least since the ’60s and probably before that, have always been active politically. This is the time when young people go through a process of politicizing their identity; there’s a stage where you’ve just become aware of the injustices and you’re trying to figure out how to be the right kind of person or activist or however you want to define yourself. From a developmental perspective, this stage is accompanied by a lot of black-and-white thinking, and sometimes that can come across as intolerance of differing perspectives. Most people evolve out of it eventually.

Let’s talk about how renaming buildings and other spaces has become a form of activism, especially recently. What’s your take on that?

I think in some ways it’s largely symbolic. If we are willing to rename a building that carries a very prominent or historical name but comes with a problematic or complicated history, then I think it’s showing, in a very low-cost way, the institution’s commitment to inclusivity or reckoning with its own past.

Are there psychological benefits to renaming spaces as well?

That’s difficult to quantify, but, yes, some students might call it a microaggression to have to take a class in a building that carries the name of an oppressor, for example. Renaming the building can put them at ease and make them feel more welcome. Environmental factors like the name of a building play a very big role in people’s sense of belonging. You need a sense of comfort to be able to relax, open your mind, and work your hardest. If you’re constantly on alert or feeling that you’re being assaulted, it’s pretty hard to do your best work. Imagine having to study in a building named for someone who did something terrible to your ancestors. Taking an action as relatively simple as changing the name of a space can have a profound impact on someone’s well-being.

When you look at the student activism happening today, what gives you hope?

I’m encouraged because, despite the state of the world, students are endlessly optimistic. They have big ideas for how to make change. They have boundless energy. They care deeply about this world, this planet, about fairness. I was afraid that in my class they were just going to get depressed because we talk about so many problems in the world, but they don’t. They feel that there is still something good out there for them. It’s a very good sign for the future.