Big Moves

Sustainability

Smith has long punched above its weight in the fight against climate change. Here’s how.

Published January 7, 2023

WITH ITS PLEDGE to achieve carbon neutrality by 2030 and its $210 million investment in geothermal energy, Smith College is making big moves to address the world’s climate crisis.

From day one, President Kathleen McCartney has made sustainability a pillar of her presidency, describing the college’s responsibility to the overall health of the planet as nothing short of a “moral imperative.”

Beth Hooker, Smith’s director of sustainability, suggests that while headline-grabbing efforts like transforming the college’s heating and cooling system and constructing more energy-efficient buildings are essential, other work the college is doing may make an even bigger difference.

“Smith has explicitly linked impact with its mission,” Hooker says, “and is committed to shaping climate leaders who can address society’s challenges.”

If it sounds too lofty to be true, think again. Certainly, the changes Smith has undertaken to reduce its carbon footprint have already made a splash. But its research, teaching, and leadership—and the students who internalize these ideas and live them out beyond graduation—are designed to make even bigger waves.

1. We Choose the Right Path, Even When It Is the Difficult One.

When Smith joined the Climate Leadership Network’s Carbon Commitment in 2007, it put its proverbial sustainability stake in the ground. The formal commitment, made by presidents of higher education institutions, requires colleges and universities to develop climate action plans to achieve carbon neutrality and submit annual progress reports.

At the time, Smith was considering strategies that included purchasing a significant number of carbon offsets. Offsets are credits that carbon-emitting institutions buy to support actions elsewhere that remove a specific amount of carbon from the atmosphere.

In some ways, it seemed like a feasible, if expensive, silver bullet. With enough money, almost any institution could achieve carbon neutrality—on paper, at least.

That “solution,” of course, was anything but. “We need to address our own emissions first rather than shift the burden elsewhere,” says Director of Sustainability Beth Hooker, who also serves as administrative director of Smith’s Center for the Environment, Ecological Design, and Sustainability.

So, Smith went back to the drawing board and considered other options.

By 2016, the college had come up with a solution that focused on electrifying the campus through a geothermal energy project. Currently underway, the project will replace the campuswide steam heating system that burns fossil fuels with one that uses technology to harness the stable temperature in the earth below the frost line and transfer it from the ground to an energy plant and then on to individual buildings for heating and cooling. Once fully implemented, the project is designed to reduce Smith’s carbon footprint by an eye-popping 90%.

The strategy is complex and time intensive, Hooker says, but it will meaningfully address the challenges of the world’s climate crisis. It is this approach—meeting the most difficult tasks head on, and with a long-term view—that helps Smith and Smithies stand out from the crowd.

“This is our legacy—preparing our students to tackle and solve complex, urgent problems,” Hooker says.

Rarefied Air

A 2021 study published by Assistant Professor of Environmental Science and Policy Alex Barron, Maya Domeshek ’18, and Lucy Metz ’22 found that of the 11 institutions that had signed on to the Climate Leadership Network’s Carbon Commitment and already met their carbon-neutrality targets, direct reductions accounted for just 8% of those improvements, while offsets accounted for about two-thirds of the reductions.

By contrast, when Smith meets its target in 2030, direct reductions will account for about 80% of its improvements. The remaining 20% will come from the electrification of fleet vehicles and equipment, offsets, and continued improvements to the energy efficiency of campus buildings.

Smith students collaborated on The Tell of Grass, a climate-related art installation occupying a 7,500-square-foot grass field. Photograph by Gabrielle Russomagno ’85

2. We Believe Every Discipline Can Contribute to Sustainability Solutions.

The Center for the Environment, Ecological Design, and Sustainability (CEEDS) has one overarching purpose: to facilitate academic and applied experiences for students that help them address environmental questions and challenges.

“Promoting and supporting multidisciplinary scholarship and teaching is foundational to our approach at CEEDS and across campus,” says Andrew Berke, faculty director of CEEDS and associate professor of chemistry.

Berke says it’s notable that, since 2013, 28% of new faculty hires have reported doing some type of research linked to climate change or environmental sustainability. Also, with the help of grants from CEEDS, faculty members have retooled their courses to include environmental and sustainability components.

For example, psychology professor Michele Wick’s “The Human Mind and Climate Change” colloquium helps students understand how to make meaningful change in the face of climate despair. An economics class taught by Associate Professor Susan Stratton Sayre explores the question of whether people would alter their behavior if they knew the environmental consequences of their food choices. And, as part of an art installation called The Tell of Grass, landscape studies lecturer Reid Bertone-Johnson paired with artist Gabrielle Russomagno ’85 to create an artwork linked to landscape conditions on a warming planet.

Courses and initiatives like these support President Kathleen McCartney’s belief that colleges like Smith can be critical partners in the fight against climate change by supporting faculty- and student-led research and academic exploration.

3. We Aim High.

In just seven years, Smith will cut some 20,000 metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions annually from its energy ledger.

Smith College Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Plan

In seven years, Smith will cut about 20,000 metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions annually from its energy ledger. They will do this through a combination of implementing conservation measures, purchasing renewable energy, including from our existing off-campus solar array, installation of ground source heat exchange (i.e., the campus geothermal energy project) and finally by purchasing carbon offsets.

4. We Teach Students to Understand Their Power, Then Use It.

Emmy Longnecker ’20 had noticed that students often trashed perfectly good clothes, books, and furniture as they scrambled to cram their belongings into cars and storage bins in the chaotic final days of the academic year. Longnecker was determined to find new homes for these valuable items.

After methodical study undertaken as an intern at Smith’s Center for the Environment, Ecological Design, and Sustainability (CEEDS), she found ways to leverage systems and processes that were already in place within facilities management, student affairs, and alum relations. SmithCycle was born.

While students are essential to the program, she says, “I made it happen with people and within systems that already existed. I worked very intentionally to ensure that the program would outlast me,” she says.

Bins filled with donated clothing, bed linens, and other items await pickup from the Salvation Army outside Scott Gymnasium in 2021.

It has: SmithCycle was launched in 2019, and Longnecker graduated a year later. Today, the program remains strong: In 2022, eight community partners accepted and redistributed donated items at the end of the academic year.

This long-term view of problem-solving helps students become part of a much larger throughline of sustainability at Smith and beyond. They create programs that last—and improve existing initiatives to make them as good as they can be.

5. We’re an Institution Designed to Innovate at the Scale of Climate Change.

The idea of innovation is often relegated to the realm of tech stars bragging about “moving fast and breaking things.” But when it comes to solving the all-but-existential problem of climate change, it may be best to consider innovation that looks beyond Silicon Valley swagger. Here’s what makes Smith a uniquely powerful institution in the fight against climate change.

Longer Time Horizons for Change

Climate change is a thorny problem that must be addressed over the course of many years. But that doesn’t align with the incentives of many organizations that might otherwise support the effort. “These days, we have lots of institutions focused on short-term thinking, like financial markets and political campaigns,” says Alex Barron, assistant professor of environmental science and policy. “But there are fewer institutions that think in multidecadal time scales.” Smith is one of them.

Wide-Ranging Research Expertise

Addressing climate change demands expertise not just in environmental science but in areas such as economics, engineering, ethics, psychology, and policy. Smith brings experts on all of these topics under one roof. For example, during Smith’s Year on Climate Change in 2020–21, faculty offered more than 100 courses related to climate issues.

Transparency

Smith’s research and innovative thinking aren’t kept under lock and key like many corporations’ intellectual property. Instead, they’re shared widely to catalyze change. “Higher education institutions can be transparent. We can experiment and share what we learned, both successes and failures, with others,” Barron says. “When others don’t have to reinvent the wheel, we can make these big transitions more quickly.”

6. We Solve Problems at the Systems Level.

By the time they arrive on campus as first-year students, climate-savvy Smithies already take plenty of carbon-neutralizing actions: They minimize their use of plastic water bottles, switch off lights when they leave a room, and rely on reusable bags.

While every action helps, Assistant Professor of Environmental Science and Policy Alex Barron teaches students to look beyond their personal choices. “Almost all the messages we receive from society tell us to approach problems from the perspective of the individual,” he says. “But like so many problems, the climate problem is not an I problem, it’s a we problem,” he says. “Instead of focusing exclusively on individual actions, we need to change the way we build our cities, get our electricity, make things in factories, support the most vulnerable, and produce our food.”

Systems-level solutions are something students learn to implement at Smith. For example, as part of her honors thesis project, Breanna Parker ’18 worked with Barron and Susan Stratton Sayre, associate professor of economics, to set internal carbon pricing (ICP) for Smith: a monetary value on greenhouse gas emissions that Smith factors into its decision-making process when it considers building new facilities or making changes to its energy infrastructure. An ICP can help translate external climate costs into financial terms and help “future-proof” today’s choices against potential carbon tax policies.

In this way, implementing the findings of a single research project that focuses on decision making at a systems level rather than an individual level can make a far bigger impact than several lifetimes of any one person foregoing plastic water bottles.

“At Smith, we engage students in the kinds of decisions and changes that society as a whole is going to make,” Barron says. “They have the opportunity to see that they can have a real impact.”

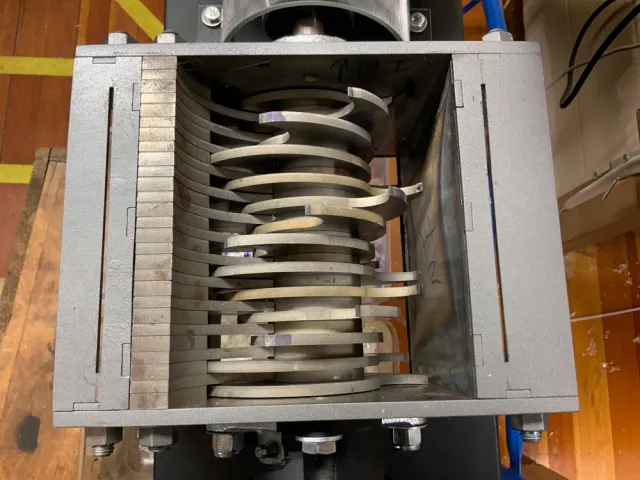

Smith students designed and fabricated this customized shredding machine, which breaks down plastic into tiny bits. Photograph by Bailey Butterworth ’24

7. We Instill Students With a “Cathedral Builder” Mindset.

When Emily Norton, director of Smith’s Design Thinking Initiative, teaches her Critical Design Thinking course, she sees student ambition up close. Students have collected stories about how people experience climate change, and they have developed eco-friendly mycelium-based materials for use in packaging and construction.

They’re big projects, Norton says, and sometimes students can’t accomplish everything they’ve dreamed up. “When students’ goals exceed what they can accomplish during their time here, there can be a moment of deflation,” she says.

That’s when she encourages them to bring a new perspective to their projects.

“I have seen students reframe their work to think of themselves as ‘cathedral builders,’” she says. “They aim to contribute to some aspects of the work and leave that work in a way that it can be picked up by the next person.”

As part of a project dreamed up in Norton’s class, a handful of students got involved with Precious Plastic, a platform that helps groups create plastic recycling machines.

In 2020, the team built a machine that shreds recyclable plastics; more recently, a new cohort built another machine that can transform that shredded plastic into filament for the school’s 3D printers.

That sense of agency is something Norton hopes all of her students take with them no matter what they pursue.

“I want students to have a lens on the world that allows them to ask, ‘Why is the world this way? And how can I reimagine it in a way that makes it better?’”

Empowered to Engage

“I want students in my classes to feel empowered to engage: to write an op-ed, to elect and lobby climate leaders, to participate in a school board or city council meeting. I want them to feel confident that they can bring something to these conversations.”

Alex Barron, assistant professor of environmental science and policy

8. We Change the Default Options.

How do you get students to eat less meat without seeming sanctimonious or depriving those who really want a hamburger? Very carefully, says executive director of auxiliary services Andrew Cox, who heads the college’s dining services program.

“We don’t want students to feel like we’re taking anything away from them,” Cox says, which is why you’ll never see a “Meatless Monday” promotion in any dining hall.

Nonetheless, even without removing specific items from the menu, Smith is on track to cut the consumption of red meat by 15% by 2024.

What's New?

Numerous non-meat options. “Students will often happily fill up their taco shells with black beans even if ground beef is available,” Cox says.

More international cuisine. In many cases, international dishes use meat as a flavoring rather than as a centerpiece, as is typical in American meals. Bibimbap, for example, is light on meat and heavy on veggies and rice; chickpea tikka masala has found as many adherents as the chicken version.

Smaller burgers. Instead of the traditional quarter-pound burger, Smith now offers one-fifth–pound burgers, saving nearly an ounce of meat per patty. Students can still take as many burgers as they wish.

Last call. By putting meat last on the buffet line, Cox says, “students’ plates are more full when they get to it, so they take less, even though they always have the option to come back.”

Vegan and vegetarian options at every campus dining hall. Once relegated to just a handful of dining halls, these options are now available everywhere.

Photograph by Jeff Baker

9. We Put Our Money Where Our Values Are.

It’s easy to pay lip service to climate change efforts. But Smith’s commitment goes beyond lofty statements all the way to its balance sheet: The college has committed $210 million for the geothermal energy project.

“It’s the largest capital project in Smith’s history,” says David DeSwert, vice president for finance and administration. “It will represent somewhere between 35% and 40% of our capital expenditures over the next 10 years.”

Beyond that, the work fully aligns with the college’s mission and vision. “We knew it was important for Smith to take action on this because we believe that what we do in our campus operations reflects our values and what we’re teaching our students in the classroom,” DeSwert says.

The geothermal energy project may be the most concrete evidence of Smith’s commitment to sustainability, but it’s just one of many ways Smith uses its money to live up to its stated values, DeSwert says. “We’ve also taken actions in our endowment to divest from investments in fossil-fuel-specific [asset] managers,” he says. “We believe in taking a comprehensive approach to practice what we preach.”

Images from the Landscape Master Plan representing, clockwise from top left: accessible pathways, movable lawn chairs, bioswales, and a connection with nature. Courtesy of Mathews Nielsen Landscape Architects

10. We Make Sure Our Impact Is Both Ecological and Emotional.

Tim Johnson, director of Smith’s botanic garden, can list countless ways Smith has planned to adapt its campus landscape to minimize its carbon footprint and prepare effectively for climate change through the Landscape Master Plan.

Bioswales will intercept storm runoff and help improve the water quality of the Mill River. Meadows will serve as pollinator habitats. Already, fewer chemical fertilizers are used to maintain the grounds than in years past.

All of these projects are quantifiable in some way: numbers and acres and pounds.

But Johnson believes the most meaningful changes can’t be tracked on a spreadsheet.

For example, he points to accessible pathways that allow anyone to visit natural areas around campus. The college recently added movable lawn chairs so students can create comfortable outdoor social spaces. Strong wifi signals across all parts of campus mean students can type a paper about Thoreau’s Walden Pond, perhaps, while sitting by Paradise Pond.

The larger goal? “We want to help people form a deep personal connection with nature,” he says. “We want to build that bond.”

11. We Develop Climate Leaders With Intention.

When associate professor of engineering Denise McKahn hires students to do research with her—modeling the energy use of specific buildings on campus, say, or determining the cost of retrofitting a space with better insulation and windows—she expects them to have the technical chops to determine the right scope for the project. She knows they’ll be able to develop the right approach for the work and methodically execute those plans.

Often, the most difficult part of her mentorship is convincing her students that they have the expertise to confidently share their knowledge with others. This might mean participating in working groups, speaking with teams of consultants, or even giving a presentation to Smith’s board of trustees. “For students, that can be absolutely terrifying,” she says.

McKahn is nonetheless insistent: She sees her role in preparing students to advise and influence powerful people as being as important as any technical skill she could teach.

She coaches students through the process over time. At first, they might be completely silent in a meeting. Later, they might weigh in with a few tentative questions as they see the value of their expertise. Ultimately, they begin to understand that they have as much to bring to the table as anyone else there. “By the end, you can’t keep them quiet,” she laughs.

McKahn says guiding students through that sometimes bumpy process within the confines of campus will pay dividends in their lives beyond the Grécourt Gates. “The experience helps them transition into leadership roles much more quickly than they would have otherwise,” she says.

And while McKahn has been particularly adept at guiding her students successfully—they have been accepted at elite graduate programs at the likes of Stanford and Princeton, and have landed roles at prestigious environmental organizations around the world—countless faculty members help prepare students in similar ways. Like McKahn, they show students how to tap into their own strengths to take on larger challenges after college.

“This is the amazing story of Smith,” McKahn says. “We train students to understand that they can really have an impact.”

12. We Nurture a Community That Sets a High Bar for Climate Change Efforts.

As Smith mapped out a strategy to mitigate its impact on climate change, its path forward wasn’t always obvious.

But what was clear was Smith’s unwavering commitment to taking meaningful action, says Jim Gray, associate vice president for facilities and operations. The ultimate decision to pursue the ambitious geothermal energy project was the result of efforts from many in the community—the students and faculty who did rigorous research as well as the administrative and board members who championed the work.

Gray adds that Smithies around the world were eager to see their alma mater lead the way on this issue. “The geothermal energy project owes a debt of gratitude not just to the faculty, staff, and students on campus but to the generations of sustainability-focused alums who have challenged us, always, to do better,” he says.